Insights

Key Themes for 2022: IAM Review of investment houses’ Outlooks for 2022, Part One

Our Chief Investment Officer David Smith summarises the major investment houses’ Outlooks for 2022

One pleasure of the New Year is the opportunity to read the varied and various views of the major investment houses on the outlook for the coming year. As usual, we will make some of the best of these available to our professional clients via our portal but, in the meantime, I thought that it would be a useful exercise to try and tease out some of the common themes and their possible investment implications for the rest of 2022.

I think it is fair to say that most of the Outlooks I have read recently – many of them presumably put together in November and early December – failed to see the possibility, in the short-term, of the emergence of a much more infectious variant of COVID and of an immediate return to lockdown and semi-lockdown measures. So, I begin with a big shout out to Brooks Macdonald who led their Outlook with COVID’s ongoing capacity to surprise and the risks of further mutations. They believe that new variants could well remain a theme throughout 2022. That said, and providing that the health services can weather the present deluge of cases, there are some silver linings in that the Omicron variant is significantly milder than previous variants and, as far as the developed world is concerned, is impacting a much more immunised population than was the case with earlier waves of the virus. It has also outcompeted Delta, driving it to near extinction in those countries where the two variants have gone head-to-head.

Rather than COVID, the most pressing concern identified by all the commentators was the return of inflation.

Although there was near unanimity amongst the investment houses that inflation was not just a transient side-effect of the pandemic but was likely to be persistent and far-reaching, there was less agreement on its causes. JP Morgan, for example, emphasised that economies were already starting to bear the costs of the transition to a lower carbon economy. Amundi thought that the disruption to supply chains and consequent re-shoring were partly to blame. Aviva argued that second-round effects were already noticeable with price rises feeding back into a wage-price spiral. Covering all the bases perhaps, Fidelity cited rising wages, increasing housing costs and low carbon transition costs, as well as the impact on prices of expectations of higher inflation.

There was broader agreement on inflation’s implications for investors with growth stocks trading on high multiples expected to suffer whilst value stocks and cyclicals were pencilled in as possible beneficiaries – in other words, a classic sector rotation. Non-US stocks are likely to come back more into favour including Emerging Markets though only to the extent that their central banks are able to stop inflation surging out of control.

There was also general agreement that central bankers in the developed world are in danger of being behind the curve when it comes to dealing with the inflation risk. Much of this is down to their extreme reluctance to do anything that threatens a recovery from the pandemic – hardly surprising given that the aftermath of the global financial crisis necessitated so many years of emergency support in the form of quantitative easing and other measures. Whilst most investment houses agreed that there has already been a fundamental regime change to tighter monetary policy, there was disagreement over the timescale in which it would play out. Neuberger Berman, for example, expect a decisive move up in rates. JP Morgan, in contrast, think rates will go up slowly and movements will be well signalled in advance. However quick or slow the adjustment, most do believe that we will avoid a taper tantrum of the type that spooked the markets in 2013, not least because households and economies are much better placed to withstand a round of tightening now as compared to then.

Investment-wise, a rising interest rate environment is nearly always bad news for bonds. Bond houses, possibly talking up their own books, are urging investors to: stay short; think about floating rate issues; and look at tactical opportunities thrown up by the adjustment. Asset allocating houses are tending to recommend clients reduce fixed income exposure altogether with several emphasising alternative assets as a source of relatively safe and uncorrelated returns.

Another area of near complete unanimity is climate change and wider ESG issues more generally with all agreeing that such matters will be even more mainstream in 2022 than previously.

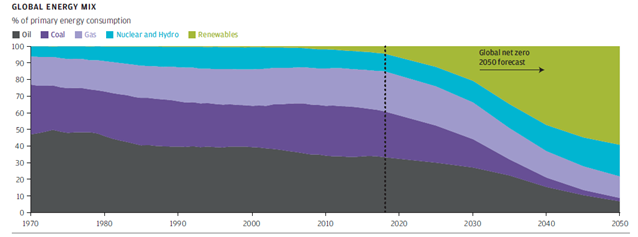

We can certainly expect more rules and regulations to be imposed by governments – especially in the wake of COP26 – but also a wider involvement of the private sector too as more and more spending is committed to the transition to a lower carbon economy. JP Morgan’s graphic from their Guide to Markets for the 4th quarter of 2021 gives some idea of the necessary changes to the global energy mix alone if the world is to achieve net zero carbon by 2050:

Figure 1: The Global Energy Mix to 2050 (Source: BP Energy Outlook 2020 & JP Morgan Asset Management’s Guide to the Markets – UK & Europe, Data as of 19 November 2021)

The implications for investors are harder to tease out with the eventual winners and losers still difficult to fathom. Overtly green and low carbon investments will no doubt continue to be the flavour of the month though investors may grow more discriminating. Old economy companies in dirty industries, or those with poor ESG records, will probably be shunned. On a country basis, emerging markets might suffer relative to the more developed because of their greater dependence on fossil fuels and the higher CO2 emission intensity of their economies.

Our look at Key Themes for 2022 will continue in Part 2, next week.