Insights

The Brexit Free Trade Agreement

Markets greeted the confirmation of the free trade agreement between the United Kingdom and the European Union, on Christmas Eve, with unconcealed relief, the FTSE 100 index mounting a 6% rally over the ensuing fortnight and Sterling consolidating its recent gains to end 2020 at a year-high against the US Dollar.

To be fair, some of the stock market’s gains were down to a global rotation out of the technology sector and into the sort of financial, materials and energy stocks that dominate the UK index, but there was also a significant rerating of British blue chips as they began to catch up with the post-start-of the-pandemic performance of other developed markets and as some of the uncertainties over the country’s terms of exit from the EU were finally dispelled with only a week remaining of the transition period.

Lest we all become too carried away at the thought of the UK escaping the worst consequences of a ‘no deal’ hard exit, it is worth looking at some of the implications of the freshly-signed agreement.

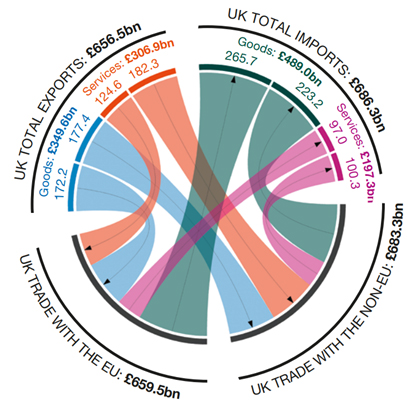

First, the agreement covers only the trade between the UK and the EU in goods, not services. Whilst the UK carries out more trade in goods than services, we run a surplus in services compared to a deficit in goods – this is true for trade both within and outside the EU. Looking for a graphic to illustrate this point, I happened across the following circular flow diagram from the most recent ‘UK Trade in Numbers’, published by the Department for International Trade and setting out the position for 2018:

Figure 1: UK Trade with the EU and Non-EU (2018) (source: ‘UK Trade in Numbers’, February 2020)

Note that, for 2018, there was a surplus of £27.6 bn on trade in services with the EU (£82 bn for non-EU trade) as against a deficit of £93.5 bn on the trade in goods (£45.8 bn for non-EU trade). At the risk of being cynical, and given how hard it has been to make an agreement with the EU on goods where we trade at a substantial deficit, imagine how difficult the negotiations covering services might prove.

Second, and although the UK will avoid tariffs on the trade of goods with the EU as a result of the agreement, it will still face significant non-tariff barriers – border checks, customs declarations, labelling requirements, rules of origin checks etc. Indeed, so significant are these non-tariff barriers likely to be, that the Bank of England had estimated that they alone would be responsible for 80% of any decline in traded goods between the UK and the EU in the event of a ‘no-deal’. Capital Group, for their part, have calculated that the new ‘trade friction’ will likely depress UK-EU trade by around a third and reduce UK GDP by 5% to 7% over 10 to 15 years compared to what would have been the case had the UK remained within the EU.

Third, and whilst the UK has made rollover agreements to continue trading on the same terms as the EU with 60 of the 70 countries and trading blocs with which the EU has agreements, comprehensive free trade agreements will need to be made with a number of important trading partners including, the US, China, India, Australia and New Zealand. These will take a long time to conclude and are likely to require more trade specialists than the country currently possesses.

So, and although the market has given a warm welcome to the Christmas Eve agreement, significant challenges remain for the UK to negotiate in the years ahead. Ultimately, these might lead to the sort of economic restructuring away from an over-reliance on the financial sector, housing and consumer spending that many argue is necessary but the UK will have slower growth in the short-term as a result of Brexit and, in the wake of all the spending on the pandemic, even less room for manoeuvre.