Insights

Do I need to worry about inflation

“Do I need to worry about inflation?” is a question we are being asked more and more at IAM Advisory in recent months.

It is hardly surprising given the levels of fiscal and monetary stimuli currently being deployed by governments to support their economies through the COVID-19 pandemic. No doubt recalling their monetarist theory – remember Milton Friedman’s, “Inflation…can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”* – investors are naturally concerned that a further round of quantitative easing, with its concomitant massive increase in the money supply, will inevitably result in higher levels of inflation.

It is true that, everything else being equal, economists would expect an increase in the money supply to result in a rise in the rate of inflation; it’s just that everything else is rarely equal, especially in situations like a pandemic, where a sudden exogenous shock disrupts demand.

Recall the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 and after, when governments pumped money into the system through round after round of quantitative easing? Did that lead to a sharp rise in inflation? No, not at all. The banks just used the money to improve their reserves and it did not work its way into the wider money supply. In other words, the increase in the money supply was more than balanced out by a reduction in the speed the money flowed through the economy (‘the velocity of circulation’ in economist-speak) and the net result was continuing low inflation.

Should we expect the same this time around? It is true that the banks are in a much better position than they were in the depths of the last crisis. They are much better capitalised now so rebuilding their reserves shouldn’t be such a factor. But, and certainly in the UK, we have seen most banks withdraw their low deposit ‘first-time buyer’ mortgages, so they are taking steps to bring down their risk in preparation for more difficult times ahead. We have also seen households in the UK ramp-up their savings, to 8.6% of total income in the first quarter of 2020 (from 6.6% in the previous quarter) even as they only prepared for the impact of the virus – most observers think it will have risen significantly higher in the second quarter. Both these developments should act to restrain, rather than unleash, inflation.

What about those long-term forces that are so often held up as drivers of deflation in the 21st century – globalisation, demographics, the gig economy, technology, the decline of trade union power? Well, and frankly, it’s difficult to see any of them reversing any time soon. There has been talk of the pandemic encouraging countries to reverse globalisation by re-shoring – tariffs have been rising under Trump, after all; and of seeking a fairer settlement for lower paid gig workers but the long-term drivers themselves are so profound that it’s hard to see them turning around in such a meaningful fashion that it affects inflation in the short term.

This brings us to the virus’s immediate impact on the balance of supply and demand and, although there has been some reduction in supply – think of the disruption to global supply chains, this has been felt overwhelmingly on the demand side, with rising unemployment and the collapse in travel and hospitality (tourism alone represents 10% of global GDP), high street shopping and in the demand for office space. This adds up to current and substantial spare capacity in the world economy and, in consequence, a firm downwards pressure on prices.

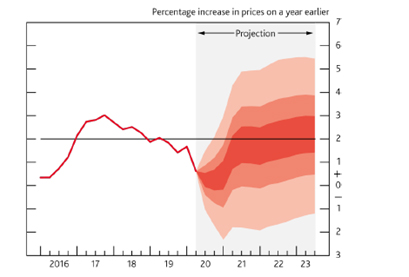

We can see the effects the authorities believe these pressures will have on the UK economy by consulting the Bank of England’s August 2020 Monetary Policy Report which has a central expectation for CPI inflation to average only around 0.25% in the latter part of the year before rising to reach only around 2% in 2 years’ time. It is best seen, perhaps, in one of their well-known fan charts from the report:

Figure 1: The Bank of England’s CPI inflation projection based on market interest rate expectations and other policy measures as announced (source: The Monetary Policy Report August 2020)

The graph is constructed so that each shade of red represents the Bank’s expectations for inflation in 30 occasions out of every 100. Their expectation is thus, that on 90 occasions out of every 100 the Bank would expect the actual outturn of inflation to fall within the shades of red whilst on the other 10 occasions, the Bank would expect it to fall outside the shades of red altogether, this under the economic circumstances prevailing when the chart was drawn.

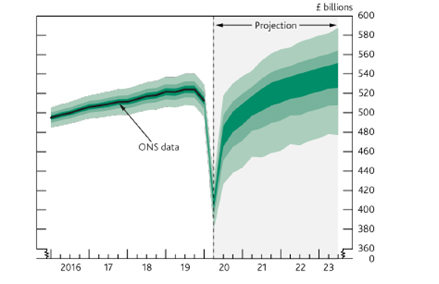

In turn, the Bank of England’s inflation forecast is based on their predictions for a whole host of factors, most importantly for unemployment (their central prediction for which is peaking at between about 7.5% and 8% later this year) and for GDP (which they still see as bouncing back in a V-shaped fashion though not quite to the same trendline as before the virus):

Figure 2: The Bank of England’s GDP projection based on market interest rate expectations and other policy measures as announced (source: The Monetary Policy Report August 2020)

It is these last projections which, in many ways, are key to the question ‘Do I need to worry about inflation?’ for, even with a sharp bounce-back, the Bank sees inflation as remaining very muted in the short term with more risk to the downside.

So, the answer to the question, is ‘No, probably not’, or at least, ‘Not for the time being’.

* The full quote is, of course: “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”